Engineering Conservation in the Southeast

A Conversation with Dana Beach

Private land ownership plays a pivotal role in today’s conservation efforts. Alex Webel asks what that looks like in the southeast while providing an overview for conservation everywhere.

Role of Private Lands in Conservation

Starting with the big picture, what role do you feel private lands play in conservation?

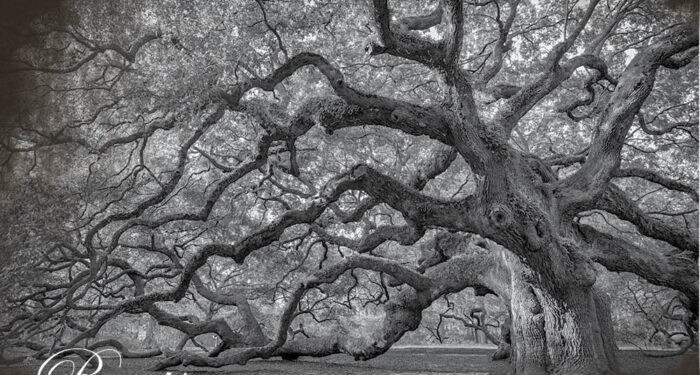

Private lands in America and especially in the East represent the majority of all land and habitat. Even in places with extensive public land, like some counties in Western North Carolina, private lands host unique habitats, and serve as ecological connections between large refuges like the Smoky Mountain National Park and Pisgah and Nantahala national forests. In most regions in the East, private lands represent 90% or more of the total land mass. It is not possible to sustain biological diversity in North America without private lands serving as the foundation of a large protected landscape.

Beyond ecology, private lands, and the traditional land uses they support like agriculture and forestry, represent the cultural and historical underpinnings of the unique character of the country, and define what is is to be “American.” Whether the historic communities of the Southern Appalachians or the Gullah people on the South Carolina and Georgia coasts, private land has defined and shaped human traditions for centuries.

As someone who has been at the forefront of conservation in South Carolina for over three decades, how has the role and responsibility of the private landowner evolved?

The pressures of growth and development are higher than ever before. It is not possible to secure a healthy, sustainable future without private lands playing the major role. Further, we have seen already the substantial and negative impacts of sea level rise. The most important resources we have to combat climate change are the soils, forests and farms that exist across the landscape, but that need to be sustained, nurtured and enhanced. Again, this is where private lands play a critical role.

More than ever before, we’re seeing our clients thinking critically about stewardship and land management. Are you seeing a similar pattern, and are there examples of this that you’ve seen recently?

Fortunately, we have seen a rapidly growing interest in habitat restoration. One of the most dramatic examples is the re-planting of the native forests of the southeast, and particularly longleaf pine. Along with that reestablishment come management needs like regular application of fire. It’s been heartening to see not only landowners adopting these beneficial management techniques, but also in some cases, local and state governments providing legal protection and financial support for that work. The bottom line is that simply preserving the land is not enough. There needs to be active and beneficial management toward ecological goals. We are seeing that at a level that we never expected 30 years ago.

In recent years we’ve seen lots of buyers enter the market as first-time owners of large, rural properties. Do you see this influx of new ownership affecting conservation?

There is a constant need to provide education to new and long-term landowners. The best way to do this is through a community of conservationists — respected landowners who have led on conservation over time, supported by competent, creative and innovative conservation organizations. The bottom line here is that landowners, new and old, pay attention to what their neighbors do. Like so many other things, opinion leaders matter. So, when new landowners come in the first thing they want to understand is how their neighbors view land management practices and why they make the decisions they make. This is a great opportunity and one that has played out well in the Lowcountry for the past 40 years. Yes.

How do family and legacy play a role in conservation decisions?

When land becomes more than simply a financial asset for the short term, but instead represents a commitment to the future of a region and the manifestation of its history, conservation begins to make more sense. The decisions conservation minded landowners make consider the implications, not just three, four or five years away, but for decades and beyond. We have been fortunate in the Lowcountry to have many multi-generational landowners, who have illustrated the financial and ethical wisdom of conserving and restoring land for the long term.

The backgrounds of conservation-oriented landowners run the spectrum – geography, politics, business, you name it – do you think there is a common thread that motivates them?

Conservation minded landowners have a few critical things in common. They have an understanding and love of the complexity and beauty of an ecological and historical landscape. They appreciate the importance of legacy, both human and biological. And they believe, in a world where selfishness is too often the dominant emotion, that they can and should make a difference in the future of the world. Aldo Leopold captured the idea of the “land ethic” as follows:

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”