Spending time in the sale barns with ranchers and cattleman, there is continual debate about the ideal cow. The common answer is: She weighs about 1,200 pounds, weans a big calf, does not take a lot of feed for maintenance, and breeds back each year. Though this is a simple answer, does not mean it is an easy one. The direction the beef industry is heading may make finding the ideal cow even more challenging.

Each fall most producers judge their herd by how big of a calf crop they weaned. In a world where pounds pay, it is difficult to argue with this judgment, but could there be more to the story? Like how much did it cost in inputs to wean your record calf crop and what are the long-term implications on the breeding suitability of the heifers that are weaned? I am going to use 20 years of data (1998-2017) on the Angus breed as my subject breed, for the fact that more than 60% of the commercial cattle in the U.S. are Angus and Angus-cross cattle.

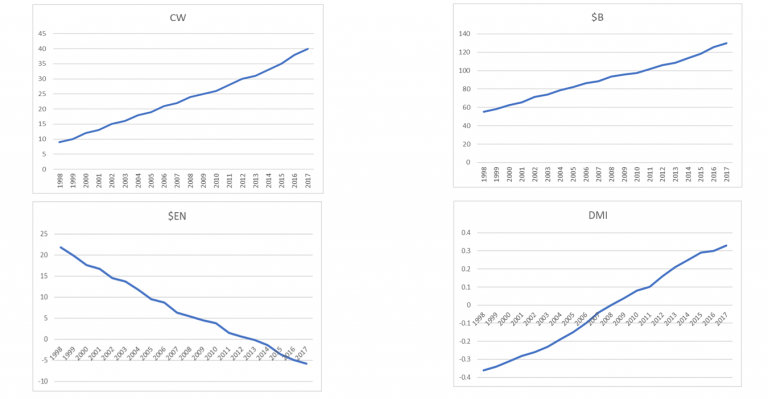

The data below was provided by the American Angus Association. It illustrates Angus genetic trends by birth year. The traits that I am looking at are carcass weight (CW, EPD), dollars beef ($B, $Index), efficiency ($EN, $Index), and dry matter intake (DMI, EPD). Though this does not capture all the genetic trends in the industry, these EPDs and $Indexes reflect what is happening on the female side of the industry.

Carcass weight and $B are what you could call performance and carcass characteristics, while DMI and $EN are more production and maternal characteristics. Cattle going into the feedlot have been reaping the benefits from this emphasis on larger carcass weight, higher dry matter intake and higher $Beef, but it seems the sword is always double sided. The females retained for breeding also possess the same characteristics, larger animals that are less efficient. In simple terms, it takes a lot more inputs to keep a 1,600-pound cow producing than it does a 1,200-pound cow.

In my travels, I have seen many producers try and take advantage of both worlds by buying maternal bred heifers, breeding their cows to high growth bulls, and not keeping any replacement heifers. Overall this seems to be a good program because they can keep a moderate-sized cow herd that takes fewer financial inputs and still wean heavy calves that perform well in the feedlot. This also leads to an economic advantage of retaining ownership for a period of time on these calves to capture more of their genetic potential, but that’s a topic for another time. With the trends in the industry noted above, these maternal replacement females are becoming difficult to source.

So where do these trends leave opportunity in the beef industry? Select females that are smaller to moderate in size, efficient (high $Energy, needing less inputs to maintain their weight) and are fertile (a unit of energy that is used for maintenance cannot be used for reproduction). These will not be the largest and showiest cows in a pasture, but time and time again, they will be the ones that do not cost an arm and a leg to feed and they breed back….leading to greater profit margins per cow. In the beef industry, we are price takers. To widen our profit margins, we cannot always count on increasing our income, but rather decreasing our inputs.

In the not so distant future, breeding females like these may be a rarity in the industry. This will open up a market that demands premiums for these sought-after females. I will admit it is a pretty attractive offer to jump on board and take advantage of these calves that will outgrow their counterparts, but at what cost? For the longevity of your operation, it may be in your best interest to stick to your guns and focus on the traits that make a cow-calf operation work, both from an operational standpoint and a financial standpoint. Try not to judge an operation solely by the weight of a calf at marketing, but take into consideration the different marketing options available and the input cost that we invest in our operations.

The links below provide the definitions of the traits and the data used for the genetic trends.